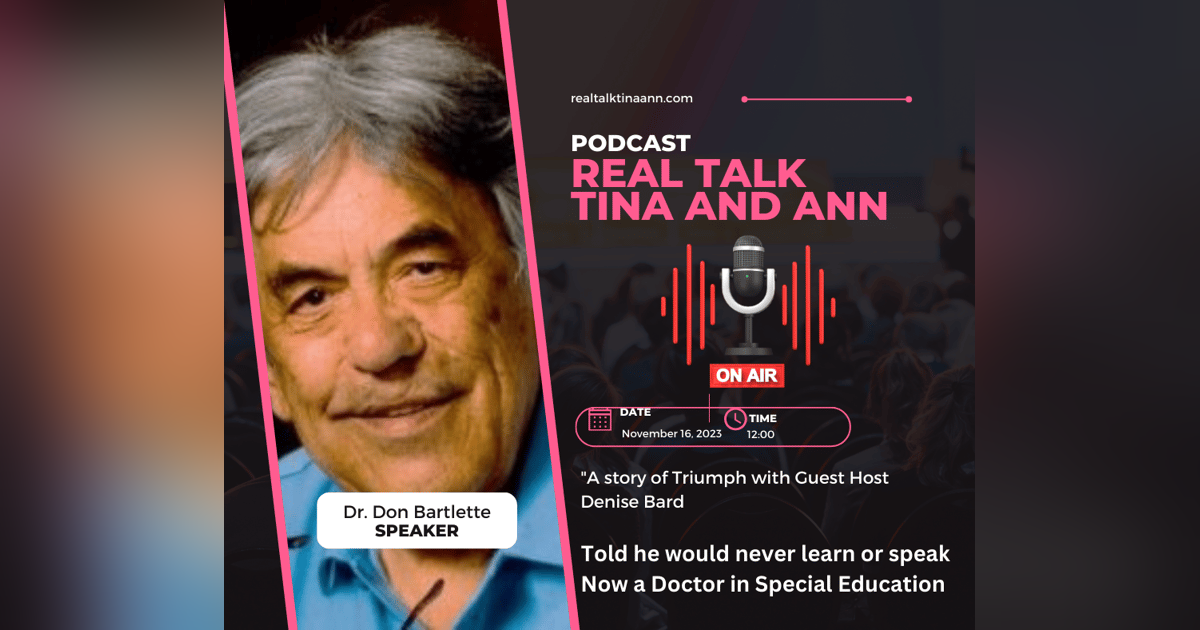

Didn't speak or learn to eat until 12: One Chippewa Indian boys quest from being told he would never speak and learn to a doctorate in Special Education

Born with a severe Cleft Palate, half a nose and told he would never learn, Dr. Don Bartlette has a story of overcoming and hope. He lived in a small shack in North Dakota. His father left him and his mother because of his disabilities. Don would steal to eat and his best friends were the rats.

"One White Woman," he states, believed in him, changing his life forever. This man who didn't even speak until the age of 12, became valedictorian of his high school and got his doctorate in Special Education to help others. All because one person believed in him.

Left to die by doctors, locked in a janitors closet by his teacher, tied to a tree by peers, this man shares a tear jerking podcast of hope and resilience and how that one woman taught him what a shower was, how to eat, and how to learn.

Listen to his main message of LOVE as he states that Hate can be Overcome by Love. Don talks about his wife, his kids and the house he lives in today. Listen to why he left his political party and his church but still, in spite of it all, has maintain his faith.

This episode reveals racism, judgment, perseverance and love.

The story of his life is chronicled in the book, Macaroni at Midnight.

He also has volunteered for Chick- fil-A for 36 years and is an active volunteer in his community.

Go to realtalktinaann.com and leave us your email in the contact section and you will get a special message from Ann. Leave us a voicemail on our website and you might end up on our podcast.

Follow us on Tina and Ann's website https://www.realtalktinaann.com/

Denise Bard's website: https://denisebard.com/

Facebook: Real Talk with Tina and Ann | Facebook

or at: podcastrealtalktinaann@gmail.com or annied643@gmail.com

Apple Podcasts: Real Talk with Tina and Ann on Apple Podcasts

Spotify: Real Talk with Tina and Ann | Podcast on Spotify

Amazon Music: Real Talk with Tina and Ann Podcast | Listen on Amazon Music

iHeart Radio: Real Talk with Tina and Ann Podcast | Listen on Amazon Music

Castro: Real Talk with Tina and Ann (castro.fm)

@Real Talk with Tina and Ann

Speaker 1:

Welcome to Real Talk. I am Ann and Denise Bard is guest hosting today. We are so excited to welcome Dr Don Bartlett Now. I have known you for decades, when I was a young newspaper reporter and had the chance to interview you and secretly told. I had seen you many times speak before that and one day I was sitting in a restaurant. I knew who you were and I had just come out of a really horrible abuse of relationship and I wanted so badly to go over and talk to you and I did get. I did get your contact information from you. It was a divine appointment. You know I happen so often when I travel.

Speaker 2:

I've been in the airport where people recognize me. I've been in the bedroom in Chicago where they recognize my voice. I had a woman running after me one time on a trip in Denver. She wanted to give me a hug and shake my hands and I'm going to miss my flight. So I kept running and she kept running and finally I thought you know what she's more important than making my flight. So it happens all the time. Here in Hannon, ohio, at the mall I had a woman the other day tell me she heard me 44 years ago, she remembered the title of my message, she remember all the details. And then that happens all the time.

Speaker 1:

Well, you're pretty memorable. I mean your story in a good way. In a good way, I mean I remember when you and I sat down and got to actually speak together for the newspaper and then I got to go hear you speak at a school. Actually, it was at a school and I'll never forget it, never.

Speaker 2:

Well, thank you. Thank you so much.

Speaker 1:

Well, so you are a speaker, social worker, counselor, consultant, advocate for minorities, for child abuse survivors and survivors of alcohol addiction, as you have lived your life with what they now call fetal alcohol spectrum disorder, and you speak on persons, on disabilities and troubled youth. You are a French, canadian, native American and, with this being Native American Heritage Month, I thought that this would be a perfect time to have you on our podcast. You speak on the psychological experiences you have had as a Chippewa Indian child, growing up with emotional, speech and physical disabilities in an environment of poverty, family school violence, juvenile delinquency, homelessness, child abuse, racism and, as we said, alcoholism. I mean you have the spectrum, you can talk about it all and you have a book chronicling your life called Macaroni at Midnight, which I have, and I'd also like to touch a little bit on one person making a difference on your life, because we talk about that on this podcast and I know that that happened to you, and also how to survive in a multicultural world. So we're going to kind of run the gamut today, but I'm just going to kind of toss it to you, don, because I am so excited to have you, because it has been so long for me that I've seen you actually face to face here, so I'm so excited.

Speaker 2:

And this is Native American Month, you know internationally, you know very appropriate that we do it today.

Speaker 1:

Yeah, Well, I'm just going to toss it to you and let you kind of tell a little bit about your story, because or tell your story, just go ahead and tell it, because this is something that everybody needs to hear.

Speaker 2:

All right. Well, let me begin by sharing with you that in 1939, the one room lot happened up in the hills of North Nehru, five miles from Canada. A very poor Native American man and woman were awaiting my arrival. It was a very cold winter night. The one room lot happened had no electricity, no running water. It was a dirt floor. My parents were very, very poor and living in a world of isolation, actually five miles away from that small white community near Canada. And on that whole winter night in 1939, 84 years ago actually, they brought me into the world. My father was a very macho man, a very wrong man, a hunter, a fisherman. He had all, basically, and he always wanted a son to be everything he was. But in my book and in the movie Backrounding at Midnight I share that I was not the boy he wanted. He admitted to their world. I had only half a nose, I had no upper lip and in the top of my mouth was a very large opening. We now call it severe cleft palate and lip condition. But in 1939, they knew very well about my disability and remember my people were poor, they were isolated and the white people in that small community did not want my family to be involved in that community. So when my father looked at my face, he made a decision that affects me even yet today. My father ran away. He hurt the handle of the fat guy with a disabled son and as he ran away, my father ran into a world of isolation and he remained in that world for many, many years. So he left me alone with my mother. My mother was a beautiful Native American woman who valued life very deeply and because of her beliefs that all lives were important, my mother hung on to me not knowing what to do. It was a tragic birth. Actually, I never saw my baby picture for 21 years and when I saw my picture it helped me to understand why my father ran away. And as he left my mother and me all alone in that one room locked cabin on her own, my mother, a warrior woman, actually put her arms around me and hung on to me, wanted me, not knowing what to do with me. However, when my grandmother heard that I had a severe disability and that my father, her son, had run off, she came up into the hills. She saw my face, she ran into that white community where they had a doctor and when the doctor came up into the hills being a man overwhelmed by prejudice and racism. He threw his hand up in the air onto my mother and he told my mother he'll never talk, he'll never learn. Send him away or let him die. They had me been a hospital an hour from here. You might want to put him there. My mother wouldn't hear that. My mother wanted me and my mother. She wanted me. My mother, she valued me and then she hung on to me. That really anchored the white doctor to have a dating woman defy him. So he went back into that small community and he told the white people that I was a handicapped, clipped, pallet Indian child and when they heard that I might never talk, might never learn, out of their fear and, I believe today, out of their racial prejudice, some of the people came up into the hills, took me away from my mother and they sent me 22 miles away to a small white hospital in another community, never brought my mother with me, they turned her away from me and that happened so often then and as they put me in the hospital when I began writing my book years later, I did a lot of research and found out that they literally left me alone on the bed in that hospital and I believe they were hoping I might die. I did not die and one day a young white male, ben O'Lean from the University of North Carolina, came into that hospital who knew his fieldwork experience, and it was he. When he saw my face, when he saw the color of my skin, he demanded that they help me. And only then, only then, they pulled the left hand side of my face over to my right hand side, leaving me with a very flat nose. For 17 years they repaired my upper lip, but they did absolutely nothing with that hole in the top of my mouth and for 17 years I could not speak clearly. I had dark circles and people used to think I was severely handicapped, that I had no IQ. This is the way people thought in the 1930s. And when they did that repair work, only then the welfare worker, a white woman who did not value me or my family, to jump me back to my mother and left me with my mother and for nine years. As a child I remember my mother so well, on her own, without any help from my father, the intimate drinking and having an affair with another Indian woman for years, a barren other gentleman outside of the barren. I learned years later and on her own. My mother can hear me for nine years going down in the river and bringing water back in the log camp and I remember her dropping the water down that hole until I might survive another day. And when my mother and I became hungry, the welfare workers did nothing, nothing, I want to make that clear. She did nothing to help my mother and me survive. So my mother went down into that white community at night time and steal food from the farmer's field so we might eat the next day. We call that poverty, we call that hunger, we call that valedictrition. Today my mother was a survivor and for nine years I remember her teaching me, use my hand to communicate to her what I was feeling, when I had an ear raker, when my stomach was hurting, when the tears ran down my face and I couldn't understand as a child why I never had a father. And so my mother went to now with me. In fact I have a picture in my book of her and me on the front step of that log cabin and she reported that the leaves falling down from the tree, teaching me about nature, about life, holding my hand and always telling me over and over one day you'll talk, one day you'll talk. I couldn't imagine, as a child, ever being able to talk, but she had faith, and her faith in God helped her to help me. And for nine years I remained home. I wasn't allowed to church, I wasn't allowed to school, I wasn't allowed in that white community, and I hate to share this, really, but I wanted to be authentic about my people and my culture. Even my own relatives Did not help my mother the way they should have, and on her own, for nine years she helped me survive. One day I was so hungry I decided to go down into that white community. My mother told me to never go there, but I was hungry. And as I went into that white community I found an area that I'll never forget, right by the railroad track. Now they call it the city of Dub Brown, and as a young child I went into the Dub Brown and there I met the only friend I ever had in those nine years, not even my own relative. We're a part of my life.

Speaker 1:

But in the Dub.

Speaker 2:

Brown I found the rats. I remember playing with the rats, running and jumping with them, pretending they were my friends. And in the Dub Brown I found food. I found warm clothing and I found comet rocks. And as I brought them home with me, I remember my mother sitting on the doorstep and, with a third grade education on her Indian reservation in the best of her ability, I remember her sounding out the words and hoping I was understanding. And then one day she asked me where are you finding all these things? Well, I couldn't talk. So she followed me one day in the Dub Brown and when she saw me playing, with the rats. My mother became an advocate for my education and my socialization. She broke every social commune in that white community when she took me to a Catholic elementary school and my mother was Roman Catholic and then she tried to enroll me. It was a nun who told my mother in front of me by the way, in front of me we will not allow him in our school. He can't talk, he can't learn, and the doctors said he might be mentally retarded. My mother didn't know what that meant, or I, but years later, when I became a member of the Presidential Committee on Mental Retardation, I told them my story and as my mother took me away from the Catholic school, she defied the social regulations even more by taking me to the public school and, fearful that they might reject me too, she told me remain here, see all the hymns, follow them into that building and then look for a number one. And she showed me what one looked like. And as I ran up to the room at Shulman what we now call child living, peer violence, rejection, bullying it they took me by my hair, they threw me into the building, hitting me, laughing at me, calling me names like Donald Duck, and like I could not talk and I'll never forget her. Never forget her. A white girl from a wealthy family, a church family, walked up to me and in front of her hair room she spit all over my face and she told me we don't want you in our school. And as I ran into their school honoring my brothers, I found the room with the number one on it. And the reason I became an educator years later is the fact that the first teacher I ever had locked me in a chatter room, closet, day after day. She would not teach me, she would not allow me in her classroom. And when I went back and forth around it two years ago, at the invitation of a librarian who took the risk of having me come home and share publicly my story, one of the people who heard me that night remembered my first grade teacher and she verified publicly what had happened to me. I remember as a child, here in my classmates, learning writing on the platform. I never did that. I was locked away in a chatter room, closet. People wonder why I became a doctor and a special education. My motivation began there. I was locked away, isolated, separated, never went in the second grade and never checked my academic record. I haven't been in my book. They put me in the third grade and in the third grade it was a teacher who told my classmates no, learn of him, no, play with him. He's mentally retarded and I can never understand what that word meant. Every time it became a part of my life. Bullying became a part of my life. The classmates took me up into the hill one day and, believing I would never be able to talk, I would never remember, they tied my hands around my back to a tree and as they hit me in my face repeatedly, the blood ran down one of my shirt. They ran away, laughing, laughing, and they left me alone up in the hill, tied to a tree. My mother had no idea where I was, what had happened to me. When I did not return home, she went looking all over the immunity. Nobody tried to help her, nobody. Late that night, late that night, up in the hills of North Secuna, tied through a tree, I began hearing the sounds of the animals. The fear, the fear that overcame me, hunts me yet today. The memory but God is a God is a powerful mystery. That night, from Canada, from a hunter-right colony, an old man, long hair, black clothes and a long beard, why he walked in the hills. I never found out. He found me. He found me, untied the rope and told me to run home. And as I ran home that night, there was a man on the doorstep with a one-room-long apartment waiting for me. He had no idea who he was and my mother told me this is your dad. This is your father. As I looked up at him, tall, tall, wrong, alcoholic, angry when I could not tell him how the blood arrived on my shirt, what my neighbor American family even today does not want anyone to know and the reason they tried to kill me in 1981 when they heard I was writing a book fearful that I might expose the secrets of family violence and child living and alcoholism. My father taught me, and what no child will ever forget he threw me, he hit me and as he continued hurting me in her desperation, my mother ran to me, put her arms around me, told him not to hurt me anymore. He took me and as he threw me against the wall, he grabbed my mother's hair. I would never forget that moment. And as he threw her into a window, she cried out I did not think. When I made it to Jordan, I ran away. I ran into that small white community and there I became and a juvenile immigrant, homeless, hungry, suicidal. Our Native young people today have the highest suicide rates in America. I understand why. I understand why I thought about ending my life over and over and over, jumping in the river. Every time I go home I go back in the river. But I remember every time I went to jump it seemed like there were invisible arms around me not allowing me to jump. Today I know why. Today I understand my God. I didn't jump, but I thought about it so many times. I was in the house, feeling soon, but I became a human without a weapon.

Speaker 1:

You were just trying to survive.

Speaker 2:

I went back and the element was broken into the library and I took a book and I remember my mother always reading to me and I wanted to read, I wanted to learn, I wanted to comprehend it and then I took that book out of my tiredness, out of my hunger, out of sleep on the floor in the library. Never, ever thinking that my life would change dramatically. In the morning I went back to my hometown two years ago. I shared this publicly. In the morning, two white policemen came in the library, taught me my hair. That is racism. They locked me in the trunk of their automobile and took me to the local jail and when, I went back home to share my story. My younger sister came to hear me. She defied the family man on having anything to do with me. She came to hear me sat next to my wife in the library. And as I shared the experience of the two policemen at Yedna Bay lecture. She stood up and she verified my life story.

Speaker 1:

She and I are very close.

Speaker 2:

Today and that night I told that community about the two policemen who removed my clothing, who sexually abused me with a belly club, damaged it, damaged it for years, myself, image, my worthiness, and that began for me a spiral that took many, many years for me to get away from. We all hate. We all hate and I began hating white people. I began hating my handicap, my data, culture. I began hating my own father. He dominated my existence for years and when my father came after me the next day, I had black and warm hearts all over me, but he never knew about the black and warm hearts inside of me as I could not talk.

Speaker 3:

And as he took me home.

Speaker 2:

I shared the movie and in my book we show a 12 year old Indian boy walking home with his tall father. And that boy began hoping that now everything okay. I mean, he came after me, he walked home with me, he must care about me. But what many of our children yet today, on every reservation, in every urban ghetto, what every child is yet experiencing? My father took me home a lot to North and as we move his leather belt he told my mother and family he is not my son.

Speaker 1:

What.

Speaker 2:

I heard that psycho-dynamic. Psycho-dynamically, the hurt turned into more hate and as I crawled in the wall, I took my father's rifle. I had seen him shoot rabbits and deer many, many times and as I took the rifle in my hands at the age of 12,. I aimed at my father and I wanted him to die. I wanted him to die and as I went to hold the printer, I couldn't understand why. Then my mother came rushing up to me, knocked the rifle out of my hands and then she told me what I'll never forget. She said we must not heal. We must not heal. Why would my mother not want to heal him? She was a victim of violence. She called her names that were unbelievable and he had affairs with another Indian who knew it. But she valued life, even my father's life, even my father's life, and was at that time in my childhood, a white woman In that small community. She heard about my being in jail. She heard about my not being in school. She had a daughter, beautiful child, came home one day and told her mother about the Indian boy Now in jail, out of school, living in a one room shack up in the hill. Her daughter told her mother how everybody makes fun of me and the teachers locked me in a closet. And when the white woman heard her own daughter laughing about me, she made a choice. And this is why I travel worldwide today, even at the age of 84, and I'll do it until I die. I want people to know that all the turmoil we're going through in our country, oh hey, can be overcome by love, one white woman, and that's why I wrote the book, that's why we're making the movie. I want the world to know that love over comes. Hey, it happened in my life Through the power, through the compassion, through the dedication, through the volunteerism of one woman, and I've been very straight with you and you know the story anyway. She was wealthy, important in that community, a church woman. There were seven churches in my hometown. None of them helped my family ever. And the white woman one day came into my life and it took me months to write that chapter and I had to remember that one moment when she put her hand on mine and, out of her compassion, looking at me, respecting me, loving me, valuing me you don, I will not hurt you. I think you can learn and I want to help you. Wealthy, wealthy, problem. A church member. She and her husband owned the only grocery store in that community. They were rich. Their daughter went to Europe. She owned a horseman, she became North Dakota potato queen, potato queen, beautiful child, but she did not value me. And when her mother put her hand up by and sent him into my home. Her daughter went to her room and never came out of it.

Speaker 1:

Oh my.

Speaker 2:

Her mother brought me into their house. I always share and now I live in the same house. I my my mansion. We live in the funeral home today and it is a mansion to me. She had. She had the mirror. We have one in the hallway. She had a living room. We have one now Four bathrooms. I'm here in the mansion. She had everything, everything carpet on the floor and in the movie they they showed the 12 year old Indian boy touching the carpet. I couldn't imagine what it was. It was warm and soft and when she saw my poverty, when she, when she recognized I wanted to learn, she took me into her dining room. We have a dining room. We have 42 members in my family. They all come home and eat my food. She brought me into her dining room and I'll never forget. She told me you might be hungry, eat my food. I can't believe it. Banana milk, bashed banana, gravy, corn. And she told me to eat and I did not know how to chew my food then and all went down that hole automatically. Nobody ever helped. My mother Helped me learn how to chew my food. It was that white woman and she took her hand, gave me a fork and, holding my head. She began teaching me how to put the food in between my teeth, how to chew the food. I thought she had a problem. I really did, and then I began feeling her love and then I began learning how to chew the food. She began telling her husband and her daughter he's not retarded, he can't talk, but I know and learned. And they began laughing at her. Her husband, her husband, a man of the church, told her either he goes or you go. I heard it and I heard it. And she looked at him and said I will not send him home, we will help him. And for years she habbed here on her own, by recommendation, by learning. I learned how to eat, I learned how to drink without the milk coming through my nose. She taught me, I learned how to read from her. She let me have all of her books and she was phenomenal with me, like my teacher Shana, that she began reading to me, helping me explain If you ever come into my home in North and in Ohio, I have books in every room of our house, every room. I have books in my garage, hundreds of books I love to read. Yet today I read all the time. Well, you really value learning who fostered that desire to read and learn. I'll never forget her. And then one day she violated the social commitments and my mother had none. She took me back into school and, using her, her prominence, using her authority, using her wealth, using her power, she told the school he is not retarded, he is learning and you will help him. I mean, she knew everybody, the small boy, the mayor, the county commissioner, the welfare worker, and she knew what was happening. And my teacher told the white woman in my presence, which I have never done when I became a teacher, when I began teaching, teaching how to teach my wife, in fact, was my intern and I taught her how to work with head to head. You never taught in front of them. My teacher told the white woman well, he smells like an Indian and I don't want him in my classroom. The white woman was astounded when she heard her own people and using race, she took me home and did the movie and in my book. One of my favorite types with the white woman is when she told me you may use our shower. I didn't know when the shower was, never had one. And then she told me verbally go in that room and I'll be soaked and shampooed and just wash your whole body. 12 years old, native American poverty overwhelming my childhood, I walked into her bathroom and as I walked out of her bathroom, in the movie we showed the 12 year old Don Martin, soaked and shampooed. All over my clothes, all over my shoes. And the white woman sent me gently by my mind. We have a lot to learn. And as she began learning from me, I learned from her. Back around the midnight. Tell the story. I'm a white woman putting a cloth on my nose, putting a mirror under my nose and with her hand on my shoulder and her food in front of me. Food motivates children to learn and survive. It was her food that motivated Don Martin. And as she put her hand on my shoulder, day after day, week after week, but year after year, what the welfare department never tried, what the medical people would not try, she taught me how to move my tongue for the first time in my life at the age of 12. She taught me how to make the air out of my lips rather than my nose, and for years I began learning how to make sounds. And back around the midnight, tell the world today that one night she told me run home, show your mother and father what you're learning. I shook my head, though I wanted nothing to do with my father. I was afraid. But she told me, don, your mother loves you. I met her, I talked to her and she did. She did, and that night, around the midnight hour, as I ran home, I was fearful of my father. My mother welcomed me. She knew the white woman was helping me. She had a hot bowl of macaroni waiting for me. And as I picked up my fork, as I put the macaroni at midnight in between my teeth, that was the moment my father sent to my mother how do you learn that? And my mother sent Abraham, the white woman in town. She told me one day he'll tell me this is your son, abraham. He needs you. And that was the moment I put my tongue in the right place. I made the air flow, remembering everything the white woman had taught me. And that night I made a sound, pointing at the macaroni and as my father heard me trying to talk, I thought, when I never thought would ever happen, he and my mother went into the white woman together. They crossed the bridge from Indian culture, from poverty, from hunger, from out on the, from childhood and from family violence. They crossed the bridge and both of them met the white woman in her plan to help me. And that macaroni at midnight became the story of the white woman engineering, networking with all the community agency, welfare department, county commissioner, the mayor meeting here in clinic, the doctor, and for many, many years I received special therapy and I learned how to talk in the manner I now speak. And as I began speaking, the white woman hired me to work in the grocery store and I became the first Native American to be employed in the white man's business. She taught me how to put groceries in the shelves, how to mark the prices on them, how to deal with the products, everything I needed to know. And as I became employed, her husband began moving away from him prejudice when he saw me becoming a value employee and I shared this with all of my Native people internationally and I want them to know. You have to have a work ethic. You survive today. You have to have one. And as I showed him I wanted to work. And as he began understanding that academically in the high school I was learning, I was learning and he hired me. Give me the bookkeeper from the grocery store I'd heard of trusting me with their money, with the numbers, working with internal revenue, making sure that they were doing everything they needed. I became a trusted employee and he began seeing the impact of her work. And as I became able to buy my own clothing you pay for a haircut to be a part of my high school I began working at other enterprises. In fact, I tell all of my children today I had five jobs in high school. Five. I always had money, I had nice clothes, my hair was cut and I began unfortunately believing that if I were white I would make it. And I began wanting to be white and I made an. I became the first head, the head Native American valedictorian of my high school. And as I began, that was raining what I could do. The white woman challenged me even more and she said Don, I think you should go to the New York University. With my new speech, I told the white woman then no way, I want to live with you. I want to work in your grocery store. I don't want to leave my mother. And the white woman said Don, you are intelligent, you have a future. Don, you can be anything you want if you went in the university. And then she said if you go, I will mail you food. And then she did. She did. I have one chapter in my book, thai Nong Serial from Canada. She will mail me cereal from Canada. I never went hungry at the university Three universities became a social worker, became a counselor, became a therapist. And then one day she said Don, why don't you become a doctor? I think you have it in you and that's why they now call me Doctor Bartlett. He hates me in special education and as. I went into the university, I began passing from white. I have a photo in my book of me in a suit with a white shirt that I wear in a hat, passing from white. And I made it at the university. I made it Outstanding social worker, senior big band on campus, became popular president of my social work club. There wasn't anything I didn't knew at and I thought I was white. I wasn't a new white. I left my name out there. I left my family behind me, always helped them financially, always helped them financially, but I didn't want to be Indian ever again. And unfortunately for me, being a victim of sexual abuse and child abuse and having an alcoholic father, I began that same journey as an alcoholic at the university. I cannot tell you how many times I was drunk and yet academically I won the highest honors at my alma mater all three of them. But I was an alcoholic and I share in my book a very different experience for me, and that's when I became involved with a beautiful, white, wealthy university student and turned her into my life, turned her into my heart and introduced her to alcohol, and today she's no longer a woman. She died of alcohol and I ran away to California, san Francisco and there in 1964, I became a part of the American Indian Movement, a revolutionary organization. I wore a red medana but by here from long, went back to my native culture out of A-Hunter and in San Francisco I became an underground Billington revolutionary. It hurted many, many people. I remember we broke into the National Republican Convention and on top of Nob Hill one day when Goldwater wanted to be president and his wife Pavey were walking into the hotel. I walked up there and I smidped in her face and I remember Miss Goldwater walking at me and she said what have I ever done to you? And I don't even know you. I shouldn't tell her about the white girl in my hometown who smid in my face. In that interest and psycho-nedemically the child turns into the adult. I'll never forget that moment. And it was in San Francisco where they saw me one day, drunk out of my mind, on the doorstep of Race and Zero, the largest in Negro in San Francisco. And when they put me in the hospital it was a Jewish psychiatrist who interviewed me and he said Mr Bartlett, I have the feeling you're running away from something I would not tell you, I couldn't tell you, I didn't want you to know, I didn't want anybody to know. And then this psychiatrist said to me I think you need to return to where you came from and find healing. And that's when I did that. I went back to North Carolina, went back to the university, got my bachelor's degree, moved to Michigan, began working with minority handicapped children, poverty children, rejected children, children from abused backgrounds that nobody else wanted to work with. And then I became director of a residential treatment center in Detroit, michigan. That's how I met my wife. She came from the University of Michigan where I used to be a professor, part-time teaching social work principles, and she came into my office one day and I didn't know it then, but she came from one of the wealthiest General Motors families in Detroit, michigan. Her father was top band in General Motors. He ran the whole worldwide energy program. I didn't know that then. And as she came into my office one day she said I want to learn how to work with minority children. And she was beautiful, absolutely gorgeous university student. And as I turned her into my program, teaching her how to work with children of poverty, children of disability, children of diversity, she won't tell the world one day. She fell in love with who I was, but not romantic. She had fallen in love with who I was professionally and out of that I married my intern before it became an ethical issue in America. I married her not knowing her background and she not knowing my background and what her family hopes I will never share. When she took me home to meet her wealthy, prominent General Motors evangelical family, I came face to face with some of the worst racism imaginable in her father. In her father, the man who never hired a black engineer and General Motors the man who helped build a church in Edison Indiana, a man who went to church facefully with his family, a man who knew in the word of God better than I do today the epitome of power. And I came face to face with him. He took my suitcase and he put it at the end of their driveway and he told my wife now my wife he is not welcome in our home. Horrible man, racist. Only last week had a family function in Indiana, a family wedding. Her brother came up to me last weekend and he said I want to ask your forgiveness for all the hurt my father and I put you through. It wasn't right, it was not. And I'm telling you, and for the last week I have been walking on cloud nine, 54 years of marriage and finally have my own in-law tell me I am sorry, I should have never treated you the way I did. He's a world famous doctor today.

Speaker 1:

Oh, my goodness.

Speaker 2:

More important than that he's from the man of God and my wife and I came back in the family wedding with a whole new relationship. That's amazing. My wife never once rejected me. She left a world of wealth to marry me 54 years ago. She rebelled against the racism. She saw something in me that she wanted me to pardon and now is the mother of eight children seven girls, one boy. All professional, all college graduates Whenever used to happen in a Native man's journey. All of my children are highly educated, highly professional and, most important of all, from me they learn the word ethic, they learn how to work. Because the woman in that small town taught me how to work. All of my children are prominent, wealthy, and this is unbelievable. Anne, this is unbelievable.

Speaker 1:

It's beautiful.

Speaker 2:

And today, at the age of 84, I still travel worldwide, sharing my life story, my faith and journey, my testimony. I volunteer for Chick-fil-A, part-time, 36 years now.

Speaker 1:

I've seen you there.

Speaker 2:

I've been away from free food, making deliveries, handing out free juke bonds, helping black populations, diverse organizations with free food, and December nights. Actually, what organization has ordered me locally for my volunteerism? And so I've been fighting all kinds of people having a tent to bed with judges, lawyers. I know people, all of us are counted, they all know me.

Speaker 1:

Everybody knows you and they know who I am.

Speaker 2:

And I just thank God every day of my life for allowing me to be who I am, for having a family that loves me, that cares about me. When I had my heart attack, when I woke up, the name were all in the room. They came to my home and put in railways and the hallways, repaired the bedrooms, so I picked them up and fixed the bathrooms. I took care of the showers. They did everything imaginable to make sure that I might survive the heart attack. Here I am 11 months later, walking, talking, flying, speaking, volunteering, all because of the family, who believe in the power of God, the power of love. And so I want to thank you for sharing my story today and yeah, that's Matt Rodney at midnight. In a nutshell.

Speaker 1:

Well, don, I mean I was fighting back the tears a lot. I mean, you know, for one thing, I have some questions, and I'm sure Denise does too, but one of the things I wanted to ask you was did you have surgeries with your mouth? I thought that I remembered that being part of this story.

Speaker 2:

I had 17 major surgeries in my childhood and adolescence, 17.

Speaker 1:

That's what I thought.

Speaker 2:

I repaired the nose. I had years of dental work, 17 surgeries and all.

Speaker 1:

Yeah, and they closed, that, closed and that reminds me.

Speaker 2:

I was in Guatemala 20 years ago. I remember my family coming to the airport and seeing me off. When I arrived in Guatemala to share my life story, I met a 17-year-old boy who had not speak with a severe heart attack. In Alberta, new Mexico, 40 years ago, I met a Dabba Ho 17-year-old boy with no speech. We had some heart attack.

Speaker 1:

Do you know my son was born fetal alcohol and he has lots of issues. And he we were just at the fetal alcohol FASD clinic in Ohio. I don't know if you're even aware that they have him in Columbus, but he was just there and they did all that testing with his speech and everything to see how he was speaking and the air and trying to teach him how to speak and everything, which he really doesn't have the same issues that you did. He's actually pretty physically okay. We got that. That was part of the testing that he had to go through, so I knew exactly what you were talking about when you were speaking about that.

Speaker 2:

I've done a lot of work with fetal alcohol syndrome all over the nation and in Canada the incidence of fetal alcohol syndrome is amazingly high, amazingly high. In Canada there is more racism towards First Nation people than we have here in America, in fact, even today. Today I've been there. I've been there Today. My people are totally isolated from anywhere. You have to fly into the reservation, the only way you get there. If you don't have money, you don't go anywhere. They are isolated. The Canadian government isolates my people so they have no contact outside of the reservation. I've been there. The poverty, the suicide, the alcohol it's like there's more racism in Canada than there is in America.

Speaker 1:

Is that why there's so much suicide?

Speaker 2:

Yes, yes, yes.

Speaker 1:

I was going to ask you why there was so much suicide in Native American.

Speaker 2:

The hunger, the poverty, the isolation, the violence, the hate. My people my people and black people have very high rates of being sent to prison for minor offensives. That's what happened. Yet today, black people have the highest rate of prison population. My people are sent in In North Dakota today by home state. The racism is unbelievable. Yet today is bad. The current chairman of the Republican Party last week had to resign for making racist remarks about my people. Today, and the governor of my home state wants to be president of our country. He's running. He's running a candidate.

Speaker 1:

I wasn't aware that that was his views. I wasn't aware that. And yeah, I was going to ask you about racism today if you still experienced that.

Speaker 2:

But apparently you Well, I know personally, but when my daughter married a black man 25 years ago in Canada, Ohio, we were forced to leave my church 25 years ago and I remember being in the mall because everybody knows me and start counting. They know who. I am Right. I remember being in the mall and my daughter and her husband, the black guy, were walking in the mall and I saw people Christian, christian, yeah, turn away, turn up. Their note that I heard the comment of that doctor Bartlett daughter. Isn't that horrible. He allowed her a very hard ban. I didn't allow her. She wanted to, she loved him.

Speaker 1:

How do you separate your faith and have such a strong faith? How have you kept your strong faith with how much racism and abuse, that type of stuff have come from the faith from people in?

Speaker 2:

the family. If I die before my wife and I hope not, I want all that money. No, If I die before my wife. I have asked her to tell the world her own story. Yes, men, pain and so on. She won't tell the world that she knows the man Don Bartlett. She knows me more intimately than anyone ever will. She won't tell you that the man Don Bartlett has come home in tears. I have come home in anger. In fact, last week was a very difficult week for me. I have resigned from the Republican Party in Ohio and Stark County and I resigned from my church Last weekend. I've had it. I've had it the racism I will not tolerate.

Speaker 1:

The prejudice.

Speaker 2:

Now I go to a church downtown. We have black people, Oriental people, handicapped people, poor people, rich people, Native American people, handicapped people. We have a church of diversity.

Speaker 1:

Right, that's the way it should be. Well, that's the way heaven's going to be right.

Speaker 2:

Well, a poor is a Baptist. No, the chairman of the Eaton Mourn in my Baptist church told me 25 years ago, when he asked my family to leave, he said, don, that is not in my Bible. I feel like you're not alone in our church.

Speaker 3:

I feel like it's hypocritical. It's very, very hypocritical anymore.

Speaker 2:

I don't know, I'm not in the wrong. Our church.

Speaker 3:

Yeah, I think that there's a lot of faith questions sometimes and it's really hard. I listen to your story and I'm just sitting here amazed and I understand I can relate in so many different ways. Obviously, I haven't walked in your shoes and we don't walk in each other's shoes none of us but it's such relatable in some of the areas that I'm in all and the fact that you are very, very faith-based and I know I've struggled with that, coming from an abusive home, coming from just not having all the support. But it's interesting when you bring in the faith I had when I was about, I guess, eighth grade, when my whole life was chaotic. I was a Catholic, roman Catholic church, going through CCD, going through everything, and there was only one nun that was incredible with me, very respectful, it seemed like she always looked out for me. But there was another nun who used to chat. I didn't go to Catholic school but she used to chat about my life at home and how I pretty much would be a cycle of things. I had a priest who, when we went to confession, talked about what I talked about in confession. I sometimes have that hard time finding that faith after you've been ridiculed and facing what you've faced with, this discrimination, not just in the world, but also in the faith that you believe in. I know my wife's question is that.

Speaker 2:

My wife has always reminded me, and my pastor, who travels with me and helps in my ministry. He's always reminded me that you and I, you and I must not look at people but look at Christ, the church. The church is not the answer, unfortunately. Jesus is the only answer. I survive every day with the Word of God and, for me personally, music, christian music. In my car right now I have a CD produced by Bill Gazer in Indiana. Every song on that particular album relates to my childhood, my family, my hurt, my hate, my survival, literally, literally. Tears run down my face every time I turn on the album, but it helps me survive. I know I'm not alone. I know I'm not alone. When I had my heart attack, one person from my former church, one, came to see me in the nursing home, one, and they have 1,100 members. Hello, I cannot be a part of that.

Speaker 1:

I need people to care about me.

Speaker 2:

I don't impact one person who came to visit me in the nursing home Unbelievable. My children were there every day. My wife was there every day, every day, and they have the love of God truly in their hearts. I know what you're talking about, but I'm running out of power. But I want to say this the word of God, the word of God is why it has helped me survive everything. My wife will verify that. My wife knows me like nobody knows me.

Speaker 3:

I mean you talked about that in your poem like praying to God and asking him To God?

Speaker 1:

I do not know.

Speaker 3:

Yes, that you do not know. I think that I relate to that so much too, but yet we still. That's all we have.

Speaker 2:

Yesterday I went down to Obvious Country and they have hired me, have been sharing my testimony this summer night at an employee's banquet, and the former Obvious Midnight Band and now a born-again Christian. He said Dr Don, I want you to share your faith openly because I have many people who think they know Christianity they don't and I want you to show them how God has changed your heart completely. And I'm going to do that. I'm not normally allowed to do that in a secular event, but he told me I want you to talk about Jesus. All you want and I will. That's what keeps me happy, joyful, alive. Yeah, I cry a lot. My Native American family nothing you do with me today. One sister only and I'm telling you she means the world to me.

Speaker 1:

Yeah, so she was the only one.

Speaker 2:

My own Native American family wants nothing to do with me and it hurts, but I have family, all of them in the world. I have family, all of them in the world. They love me.

Speaker 1:

Yeah well, they say, you can pick your family. It doesn't have to be a blood-related. So.

Speaker 2:

Absolutely, absolutely. I'm running out of power, I'm running out of voice, but I want to thank you for doing whatever you're doing with my life story and anytime I can do anything to help, let me know.

Speaker 1:

Well, maybe we can have you on again, because there's some more things that you could talk about, so maybe we could have you on again.

Speaker 2:

Well, that reminds me, ann. My second message is called Cookings for Breakfast and it talks about a time in my life when my wife almost died in the hospital 10 days and I'm left alone with five little girls and bored, and I learned how to be the head of my household, the father of my children and the lover of my wife and she almost died on me.

Speaker 1:

Thank God that that lady was there to help you. Thank God your mom was there to put her arms around you and protect you when she needed to, and thank God that she had you not kill your father. I mean thank God that that man was going through on that hill and was able to take the rope off of you and tell you to run home. I mean, god was protecting you in the midst of all this stuff. Well, the last few seconds with Don was lost in the recording and that's okay. He just thanked us for having him and we were so blessed to have him. I'm so thankful that we were able to capture all of the audio, because we did have audio problems on his end with a lot of echo, which I was able to fix. So I'm just very grateful that we were able to tell that story and allow him to be on our podcast and share with whoever is supposed to listen to his message that. I pray that it reaches them, because this is a story that everybody really does need to hear. Thank you so much for listening to Real Talk with Tina and Anne and thank you, denise, for being a part of this and, like always, we will see you next time.